TL;DR? Here’s a one-page version of this post. You can also see the code/methods on GitHub.

Programming note: This piece is co-published with Progress & Poverty, a newsletter run by the Center for Land Economics. The Center for Land Economics creates tools and research to promote equitable assessments and sustainable development.

A federal program designed to subsidize safety-net healthcare is quietly shifting tax burden onto the very communities it is meant to serve. The 340B Drug Pricing Program has become a major engine for hospital consolidation, incentivizing nonprofit systems to acquire private practices and hospitals to capture their drug revenue. Because these acquired properties typically fall off the tax rolls upon conversion to nonprofit status, the resulting revenue shortfall is redistributed as a silent surcharge on local taxpayers.

For those unfamiliar, the 340B Program lets qualified nonprofit hospitals purchase drugs from manufacturers at a steep discount; the hospital then charges patients (or their insurance) full price, pocketing the difference. This buy-low-sell-high setup is incredibly lucrative for hospitals and has caused a gold rush to join the program by any means necessary. As a result, 340B has expanded well beyond its original mandate and is now creating unintended consequences throughout the wider economy.

One of those consequences is increased property taxes. The basic causal chain goes like this:

Step 1: The 340B Program incentivizes nonprofit health systems to acquire or roll up for-profit hospitals, doctors’ offices, and oncology practices in order to access their patient bases.

Step 2: Once acquired, the physical property of the acquired for-profit entity becomes tax-exempt, significantly reducing or eliminating its property bill.

Step 3: In many jurisdictions, other people’s property taxes automatically increase to fill the gap left by the formerly-tax-paying property.

This isn’t happening on a massive scale, but it’s a big enough deal to significantly impact the communities where it does happen. Because property taxes are the largest source of revenue for local governments - and hospitals are often among the largest and most valuable commercial properties - the fiscal impact of exempting them can be huge. Further, it’s a great example of a surprising second-order effect – one that almost certainly wasn’t intended when 340B was created.

So, let’s walk through each link in the causal chain above, using a case study to demonstrate the on-the-ground impact.

A long line of studies has shown that the 340B Program incentivizes market consolidation among providers. Most of those studies focus on vertical integration, which is when 340B hospitals acquire private practices, infusion centers, etc. to make into child sites. The hospitals then inherit the patients of the acquired child sites, giving them more opportunities to purchase (and administer) 340B-discounted drugs and thus increase their drug revenue.

However, the 340B Program also seems to incentivize horizontal integration among hospitals, which is when a 340B hospital purchases a non-340B hospital with the intention of enrolling it in the program. For example, for-profit hospitals cannot enroll in 340B. However, some for-profit hospitals still meet the underlying requirements for the program (usually via DSH percentage). So, if a nonprofit hospital acquires an otherwise-qualified for-profit hospital and converts it to a nonprofit, the acquirer gets not only a 340B-qualified hospital, but also all its potential child sites and patients.

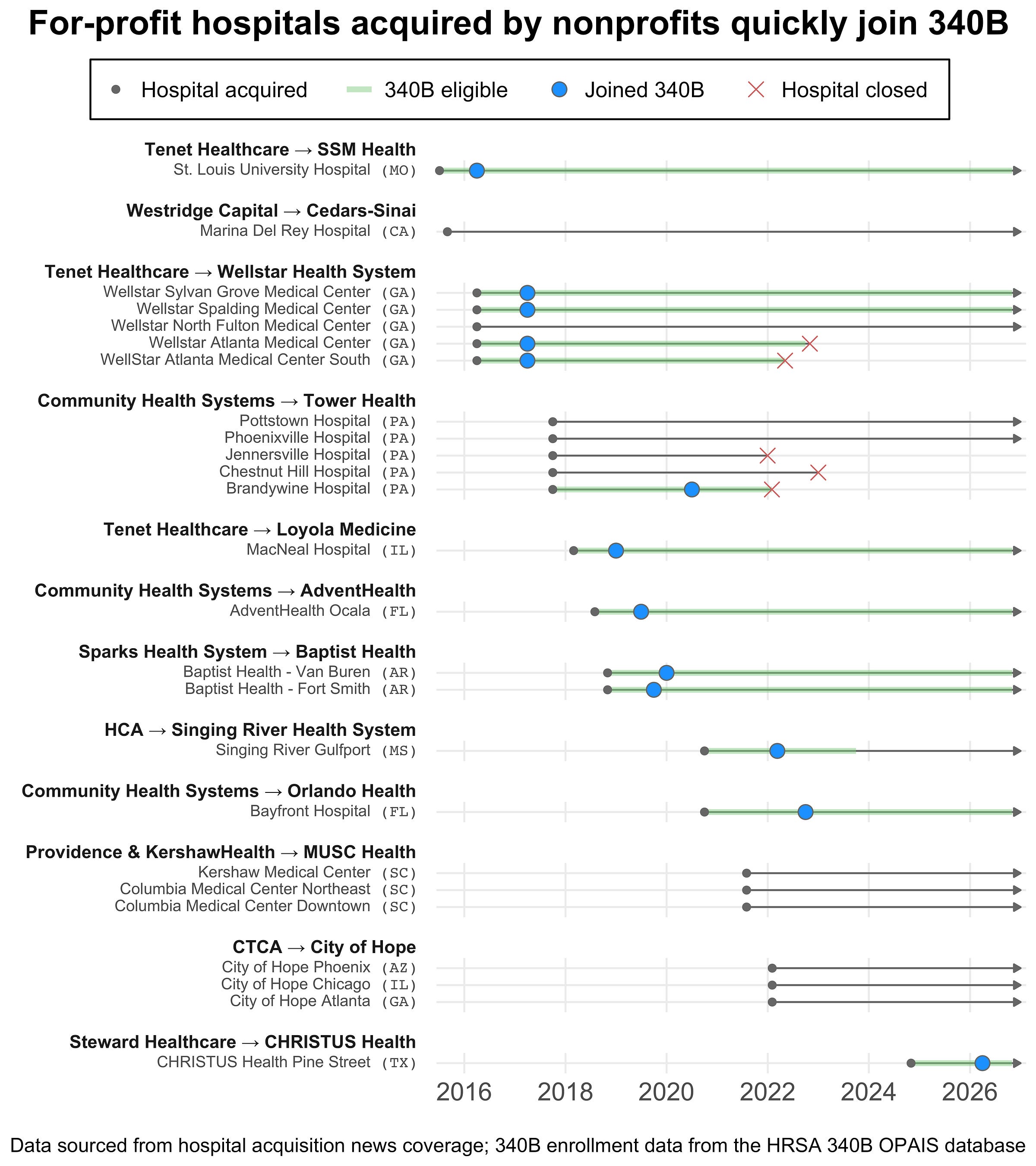

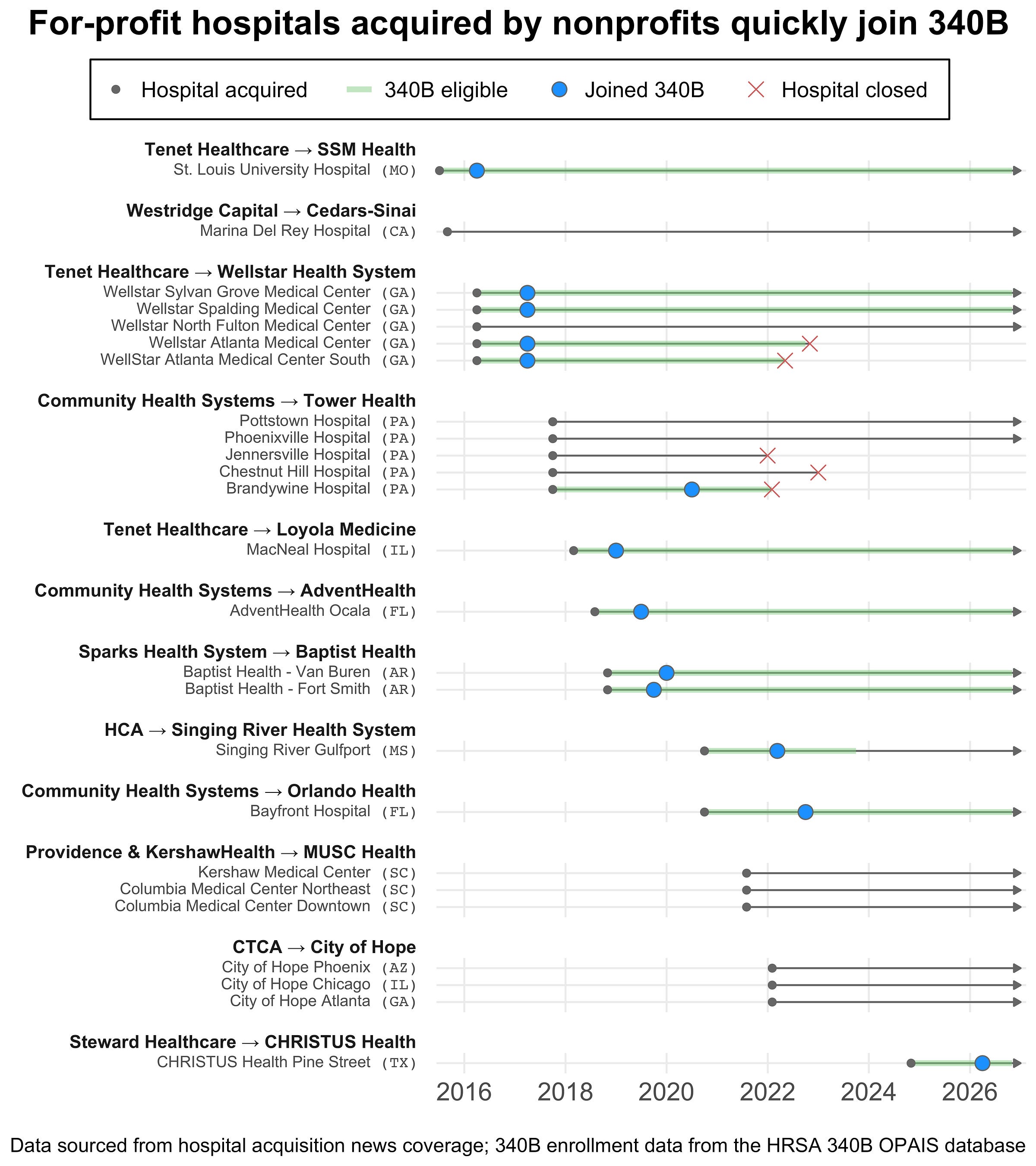

This buy-then-convert pattern turned out to be surprisingly common. Using searches of Becker’s, CHOW, and hospital finance websites, I found 25 cases of for-profit hospitals getting acquired by nonprofits in the last decade. In over half those cases, the newly acquired hospital almost immediately (within a year) enrolled in the 340B Program. The remainder did not enroll because they were not 340B-eligible even after conversion (e.g., they did not meet eligibility criteria such as the DSH threshold). Here’s the full timeline of the acquisitions I found:

[

](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!fMu2!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa334b6f3-0fed-4224-9047-4463f7cff712_5120x5760.png)

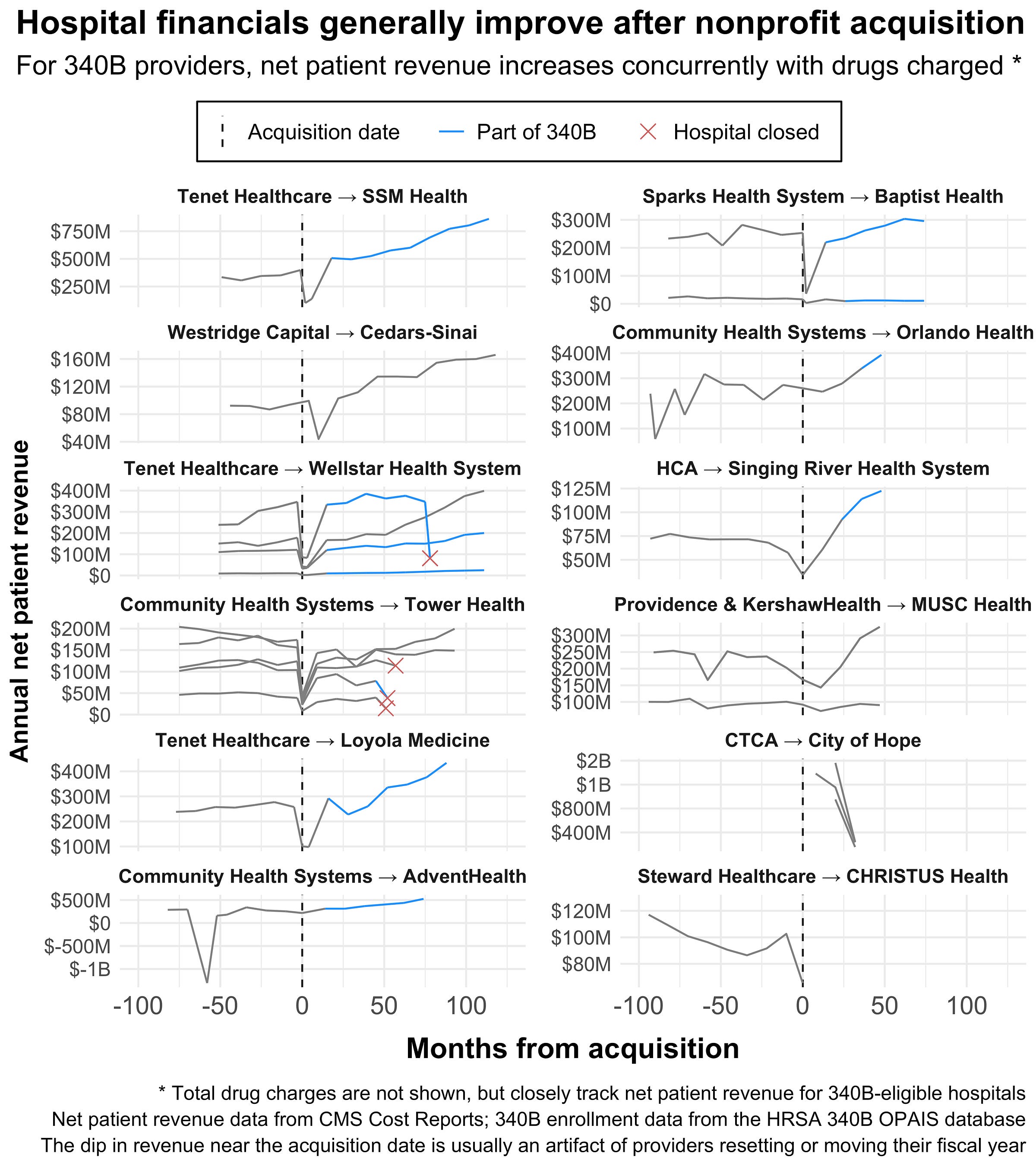

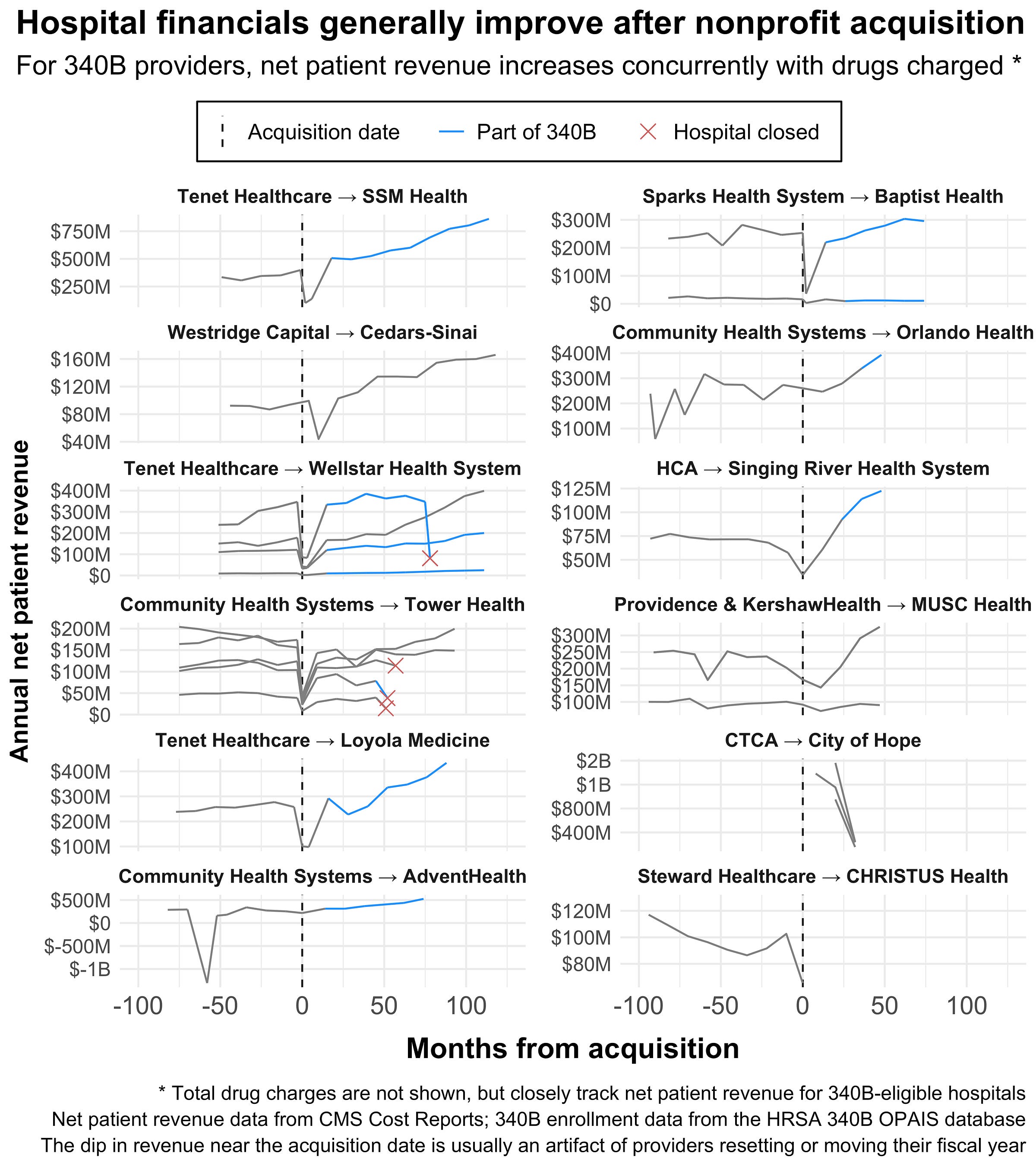

It’s impossible to know if 340B caused these acquisitions, but I think it’s fair to say that it increased their financial attractiveness and probably made some of them pencil out. To check this, I pulled each hospital’s financial performance as reported in their CMS Cost Reports.

The plot below shows each hospital’s net patient revenue (NPR) before and after acquisition. Hospitals enrolled in 340B generally seemed to have a sharp takeoff in NPR and total drug charges (not shown, but they track together), hinting that at least some portion of their post-acquisition growth was fueled by 340B.

[

](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!0H_U!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F6d3e4eee-05d9-4d8c-b45a-b4837d1f213a_5120x5760.png)

Some caveats here: the dip around the acquisition date of each provider is mostly (though not entirely) an artifact of hospitals switching/truncating their fiscal years when reporting. Further, while I tried to statistically quantify the difference between 340B-enrolled and non-enrolled hospitals, the groups here are qualitatively different enough that it’s not straightforward. Most of the non-340B, acquired hospitals (Marina Del Rey, Columbia Medical Center) are associated with a “premier” local health system or are dedicated cancer centers (City of Hope).

The downstream consequence of all this integration and consolidation is a property tax shift. As private practices, infusion centers, and hospitals get acquired by nonprofit systems, they also get removed from local property tax rolls.

How nonprofit property is treated in practice is messy, piecemeal, and inconsistent. Different states and localities have different laws around which properties are deserving of property tax exemptions. Most require some kind of exclusive use – the property must be used solely for charitable, religious, or scientific use. However, what counts as “exclusive” differs widely, and many states carve out special rules for hospitals.

This is complicated further by the complex nature of property ownership and the various commercial agreements many hospitals maintain. For example, a hospital may lease part of its property to a commercial vendor (e.g. a cafe) or use it for a non-qualified use (e.g. fundraising), blurring the line between exempt and non-exempt use. Further, exemptions for a big property like a hospital typically involve a lengthy application process. That process can sometimes be contested by outside parties or result in a payment in lieu of taxes (PILOT).

All this complexity makes it hard to measure the actual property tax impact of programs like 340B. I initially tried to determine the property taxes and exemption value of each of the hospitals in the timeline above. I wanted to put a total dollar figure on the property tax cost of the 340B Program. This proved essentially impossible. Most states have very little historical property tax data available online, and fewer still have data about tax-exempt properties.

However, here’s what I can say given the available data – all these hospitals are property tax exempt as of 2026. That’s according to records from local assessors’ websites, property tax payment portals, and scouring financial records. There’s some nuance here - many properties are partially exempt or have a PILOT, others have closed or have questionable status - but all of them eventually became exempt after acquisition.

And here’s what I can’t say with the data – I don’t know when each hospital first became exempt, how much their exemption is worth, how much they’re saving in property taxes, or how much their exemption is costing others. All that information is locked away in the historical records of ten different counties.

That said, at least some counties do maintain good enough open records to check all those things and quantify 340B’s impact. So, since a national analysis isn’t possible, I thought it would be instructive to look at a case study.

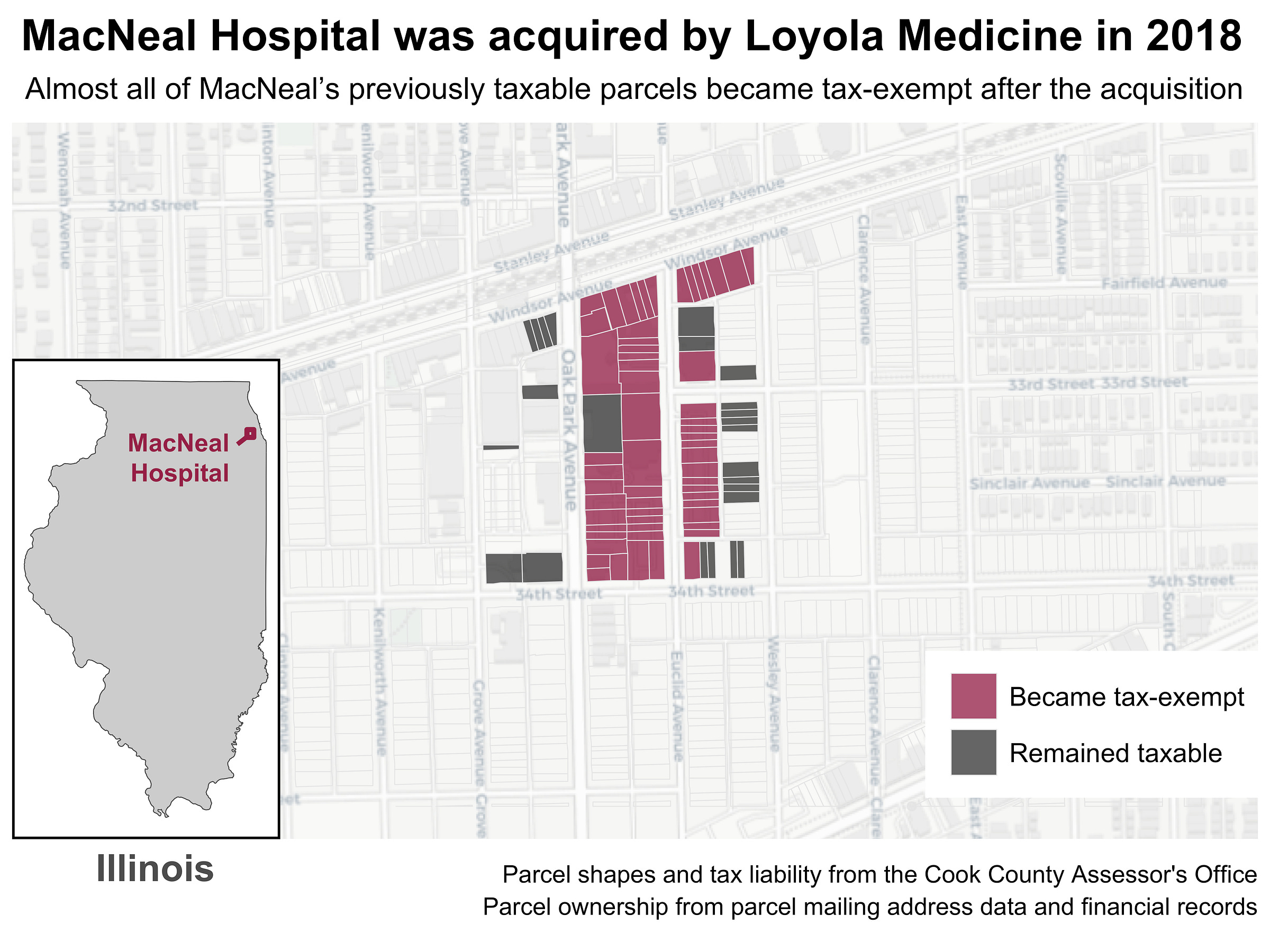

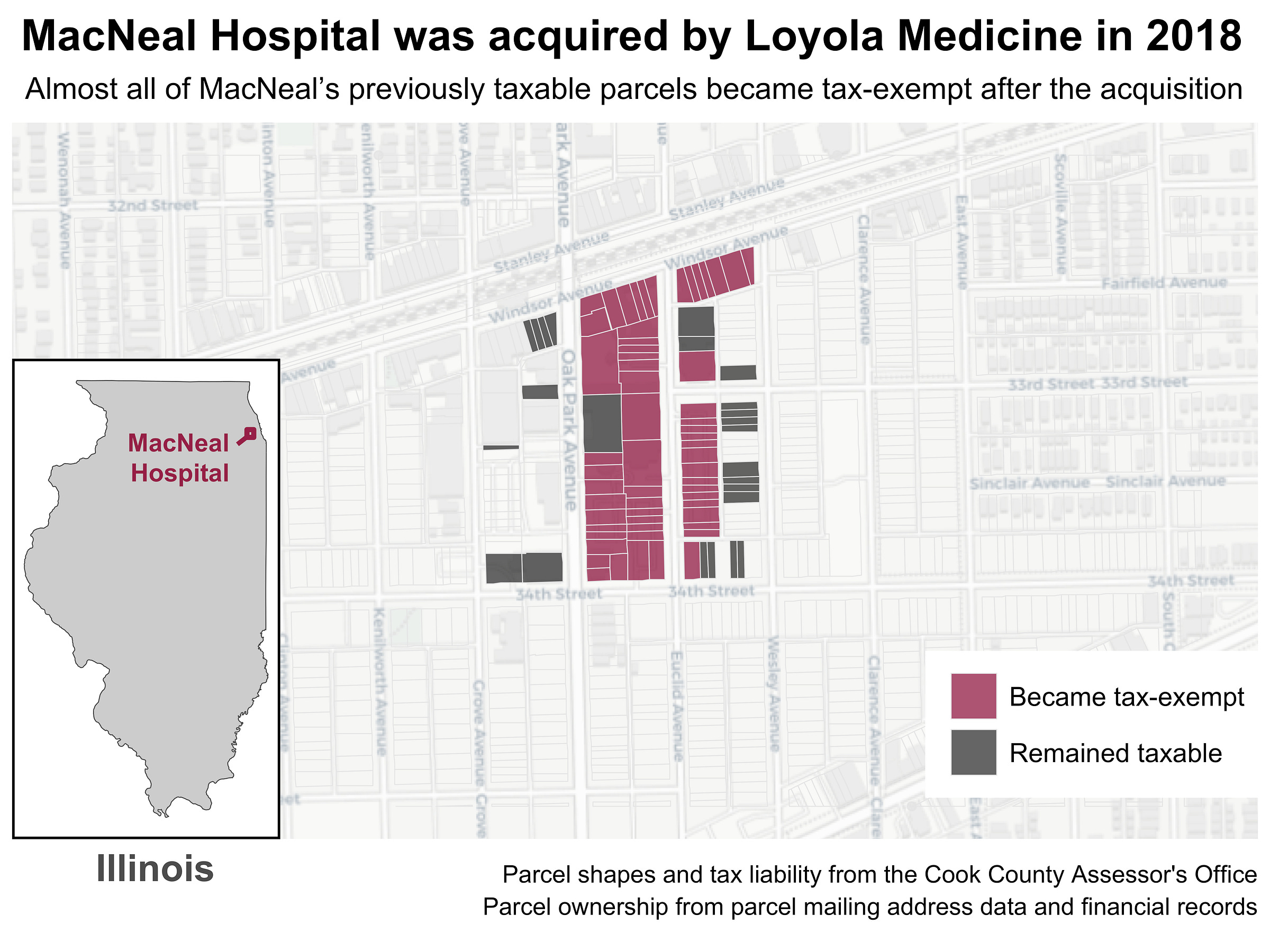

MacNeal Hospital was owned by Tenet Healthcare, one of the largest for-profit health systems in the U.S. In 2018, Loyola Medicine acquired MacNeal and all its affiliated operations for $270M. Shortly thereafter, MacNeal was granted a nonprofit property exemption by the Illinois Department of Revenue.

[

](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!0hkB!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F247a9131-7768-4ba8-9989-0adce7e470c7_5120x3840.png)

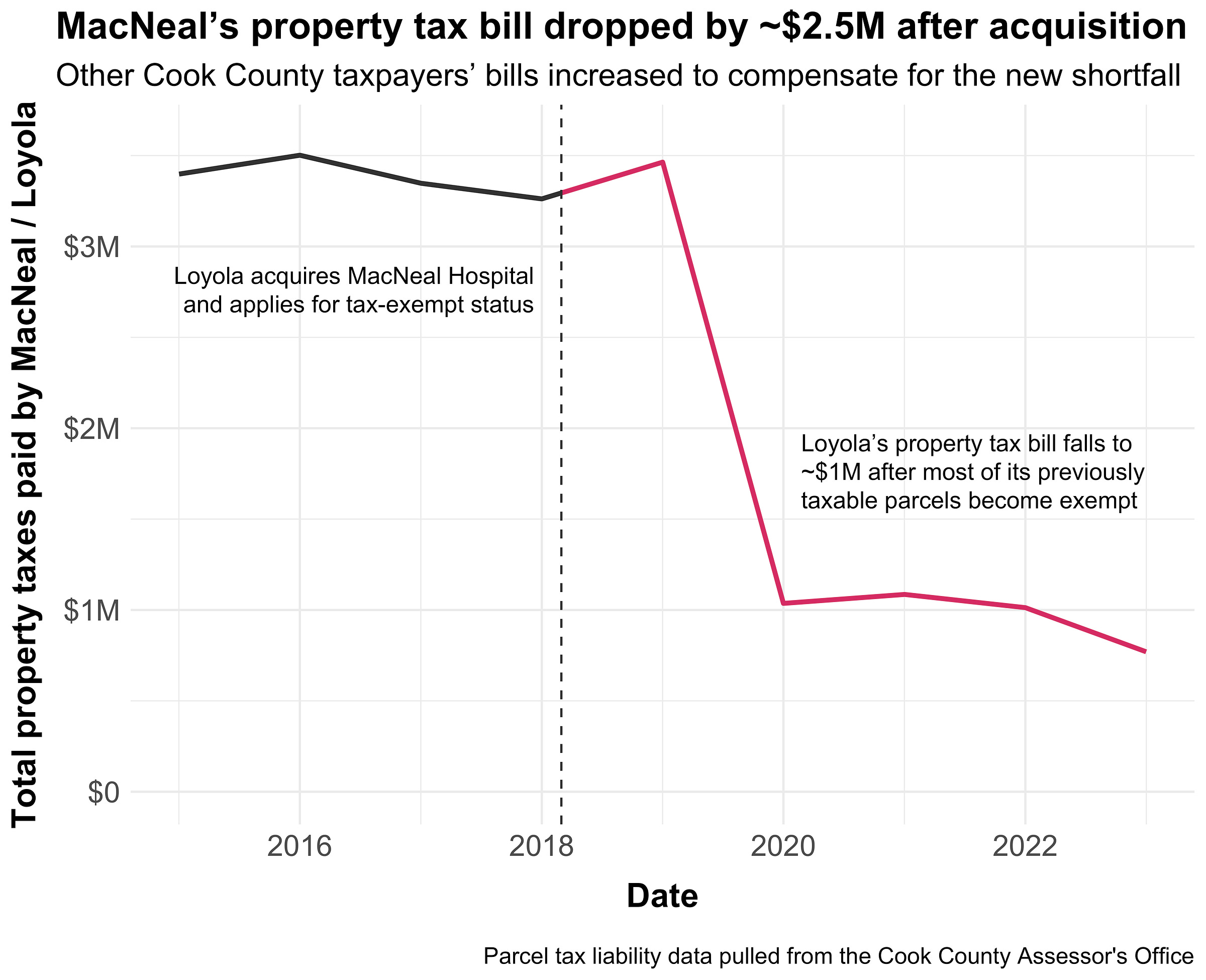

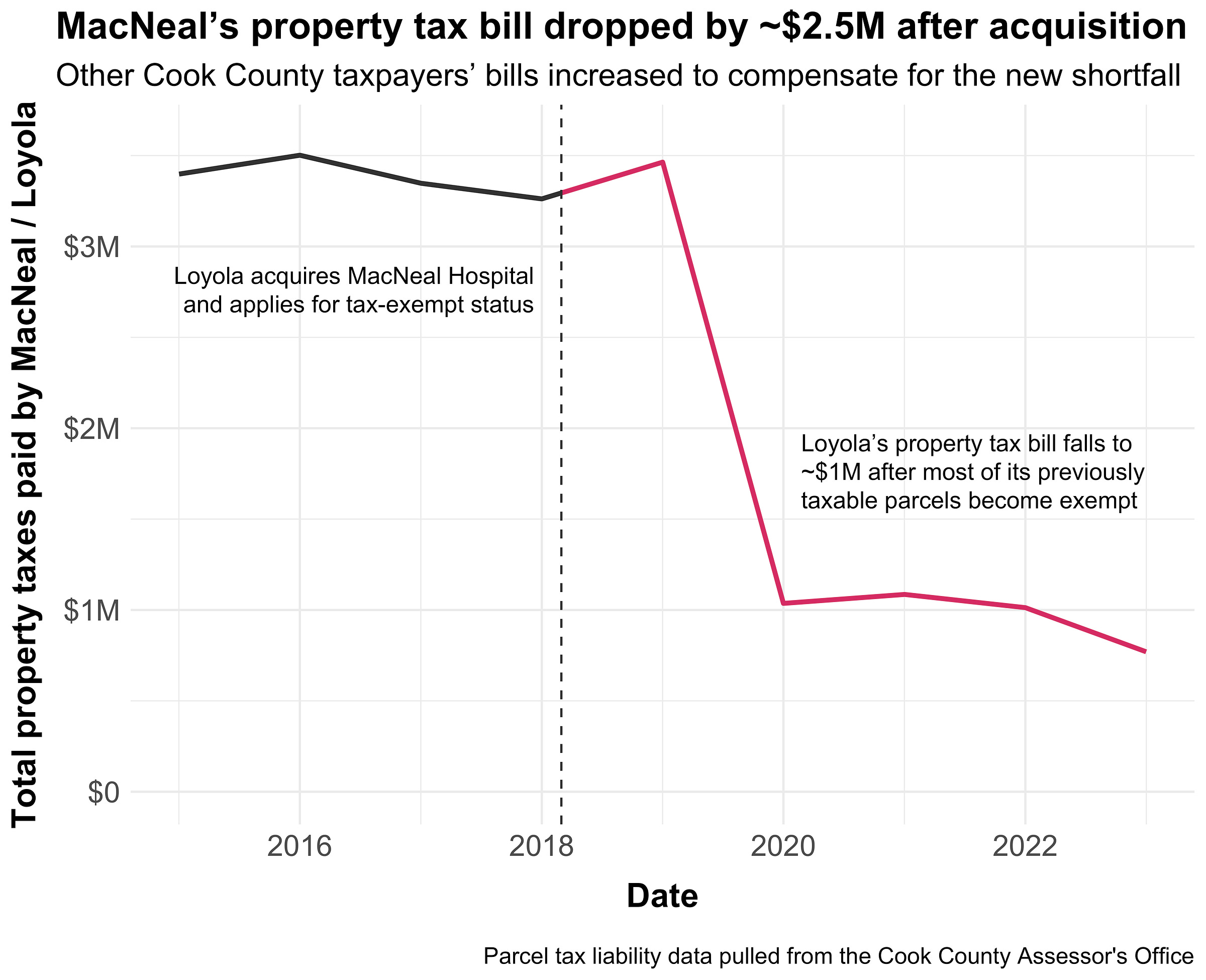

Not all of Loyola’s parcels qualified for the exemption; many were owned by the hospital but dedicated to commercial use (parking lots, offices, etc.). As such, MacNeal’s property tax burden fell, but not all the way to $0. The taxable value (EAV) of its properties fell from $23M in 2019 to $8M in 2020, resulting in a $2.5M decrease in its annual property tax bill. Here’s what that looks like graphically:

[

](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!TWe_!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F62b1dcf0-33ee-4b79-bfdf-c5ddb89272a3_5120x4160.png)

Note that I’m not saying that giving MacNeal an exemption is bad, per se. Nonprofit hospitals get these tax breaks with the expectation that they’ll provide community benefits, and most do. In MacNeal’s case, they now get a tax break of around $2.5M per year, but they also drastically increased their charity care post-acquisition - from $2.6M in 2017 to $8.4M in 2024 - according to data from the Illinois Health Facilities & Services Review Board.

However, in Illinois and most other states, property taxes are zero-sum and therefore have inherent tradeoffs. Decreasing one person’s property taxes means increasing the property taxes of others. Removing a large hospital like MacNeal from the tax rolls means shifting its substantial tax burden to nearby properties. Let’s see how that actually plays out in practice.

There are essentially three common scenarios when a large property is removed from the tax rolls:

Property taxes rise on surrounding properties to make up for the shortfall (as described above). This is typical for most jurisdictions in the United States.

Property taxes stay the same on surrounding properties and local governments have a revenue shortfall. This basically only happens in California and Oregon.

Local governments arrange a Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILOT) to prevent 1 or 2 and set a fixed payment for the property via legislation or a regulatory body.

MacNeal followed the first scenario. In Cook County, Illinois, where MacNeal is located, all local governments set a yearly revenue target called a levy. Property assessments (the base) are then used to set a tax rate which determines each parcel’s share of the overall levy burden. If one property’s assessment falls dramatically, then the tax rate increases to compensate, which increases everyone else’s bills. This system ensures stable revenue for local governments, but it also means that big tax breaks or assessment changes on neighboring properties can affect your tax bill. Here’s what that looks like as an equation, where MacNeal’s taxable value fell by $15M:

\(\frac{\text{levy}}{\text{base}} = \text{tax rate} \)

\(\frac{\$31\text{M levy}}{\$690\text{M base}} = 0.045 = 4.5\% \ \text{tax rate}\)

\(\frac{\$31\text{M}}{\$690\text{M} - \$15\text{M MacNeal value}} = 0.046 = 4.6\% \ \text{tax rate}\)

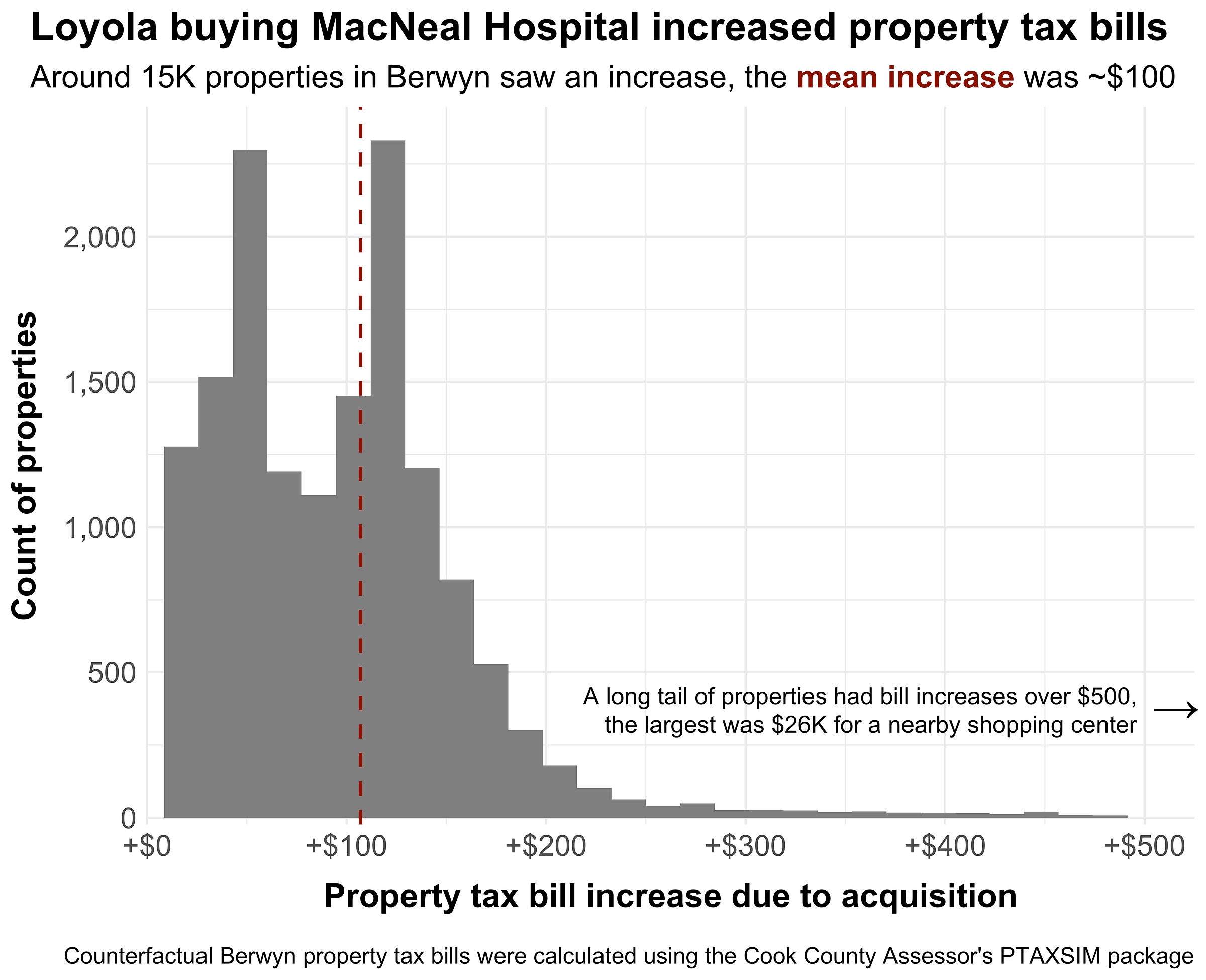

Figuring out how one property’s tax break affects its neighbors in a levy-based system can be tricky. Fortunately, Cook County has a public property tax simulator meant for exactly this purpose (disclaimer: I made this). To quantify the impact of the MacNeal acquisition, I used their tool to calculate counterfactual property tax bills for all surrounding properties, then compared them to actual tax bills. The difference between the two bills is essentially the cost that each property is paying due to MacNeal’s tax exemption.

[

](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!lwnZ!,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb1e0bd1f-8b01-474f-9abb-77c26f3de59a_5120x4160.png)

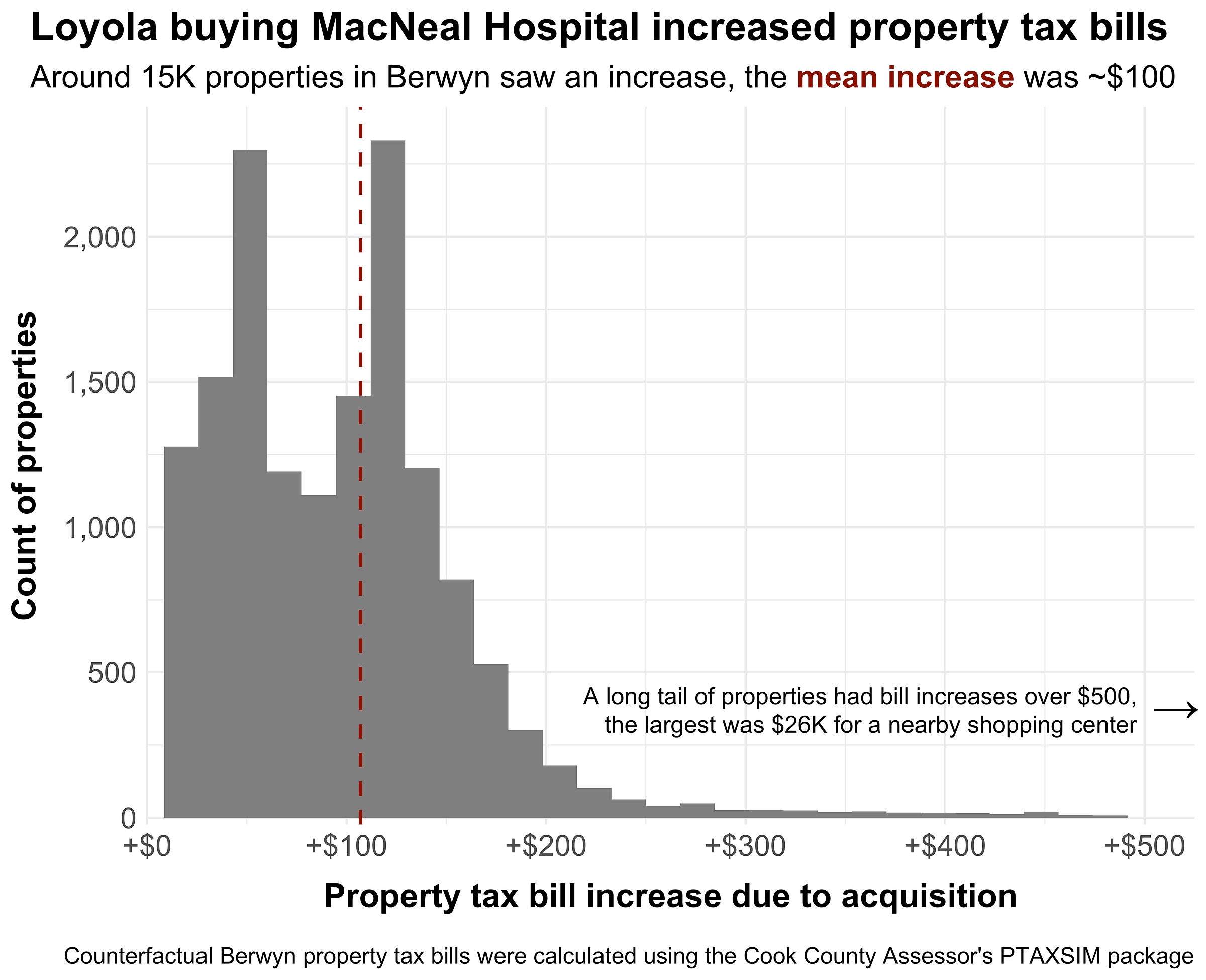

Around 15,000 properties in Berwyn, where MacNeal is located, all saw increased property taxes due to the MacNeal exemption. The average increase was around $100 annually, but a long tail of properties saw much higher increases as well. Further, the effects weren’t limited to just Berwyn. Technically, all property tax bills in Cook County rose due to MacNeal’s exemption, though spread across the much larger county tax base (1.8M parcels) the increase was just a couple cents per property.

It’s not obvious that a hospital acquisition would increase your property tax bill. There’s no line item on your tax bill that says “MacNeal exemption surcharge.” The increase just gets quietly baked into your tax rate, indistinguishable from any other year-over-year change. Most people in Berwyn probably have no idea that Loyola’s acquisition of MacNeal is partly responsible for their higher bills. The practical point here isn’t that any one household is being bankrupted by these changes; it’s that a policy lever meant to subsidize safety-net care quietly created a mechanism for redistributing local tax burden in ways most taxpayers (or policymakers) would never suspect.

MacNeal isn’t a one-off. The same basic causal chain applies to most of the nonprofit acquisitions in the timeline above: when a for-profit hospital (or a network of affiliated sites) gets converted into a nonprofit, some portion of that real estate is very likely to fall off the tax rolls.

Even if the per-property effect is small, these shifts stack: multiple acquisitions over time, plus the ongoing roll-up of private practices and infusion centers into tax-exempt systems, gradually erode the commercial tax base in the exact places where hospitals are the largest and most valuable properties.

While the actual tax impact is important, the deeper lesson here is about how complex systems route incentives in unexpected directions. A federal drug discount intended to support safety-net care became a catalyst for consolidation; that consolidation converted taxable property to exempt property; and local property tax systems turned that conversion into a distributed surcharge on everyone else’s bill. None of those steps are crazy in isolation, but chained together they produce an outcome that’s both unintuitive and hard for the public to even notice.

Nonprofit exemptions and 340B are both, functionally, public subsidies. They’re justified on the theory that the hospital will return value via charity care and broader community benefits. But those benefits (and the gains from 340B) are often diffuse, hard to value, and accrue over time. Meanwhile, the subsidy costs are hidden and nearly impossible to discern even for experts.

To preserve the intent of 340B and nonprofit exemptions without turning them into a hidden surcharge, the minimum starting point is transparency. Jurisdictions should be able to put a dollar figure on each exemption, show who absorbs the shifted levy, and compare that cost to measurable community benefits so homeowners aren’t unknowingly underwriting federal policy.